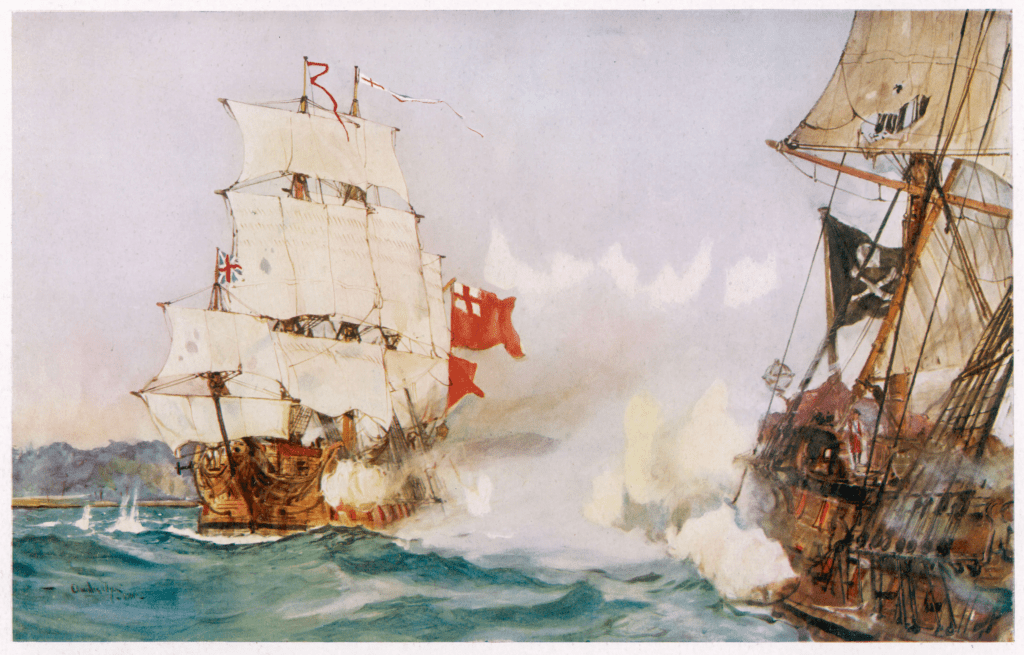

I’ve covered guns and cannon, chases, mass combat – but what would a pirate game be without ship-to-ship combat? Now on the Rules You Can Use page is:

Naval Combat Rules (14 page pdf)

For Pathfinder 1e, but easily adaptable to many others I think. It works in concert with the Geek Related cannon and mass combat rules and adds ship design and combat at sea.

I wrote an early version of this for Frog God Games and it got partially incorporated into Razor Coast: Fire As She Bears! But that work turned out pretty long and complicated, though very good, and for our game my players wanted naval combat but weren’t going to put up with 96 pages worth of it. Do get Fire As She Bears, though, it’s quite good, especially if you want to invest more in the naval combat ruleset part of your game. If you like these rules, they are directionally similar; I’ve been evolving mine over the intervening 10 years as we’ve used them to maximize flavor of our base case – small numbers of ships chasing, fleeing, and fighting with small numbers of cannon and the usual Pathfinder magic-and-monsters thrown in.

Pathfinder published some ship combat rules eventually for their Skull & Shackles adventure path but they suffer from the core problem of ships having one pool of 1600-ish hit points, which makes it either pointless to do the ship-to-ship combat and everyone just boards or, once you get high level, you swing the barbarian over there on a rope and sink it in a round. They did this because their adventure path quickly becomes PCs running squadrons of ships, not the feel I was going for.

The solution (from my rules, and in Fire As She Bears) is to break larger craft up into 10x10x10 squares and have each of those have hit points, with the added benefit of you can correlate crewmen (and PCs) to those areas. I used much lower hit points than even Fire As She Bears did – 50 hp per hull section instead of 150. In my campaign this was better suited to fast naval combats. PCs get impatient and always want to fly to the other ship; this made the PCs focus on keeping their ship safe and manning repair crews instead of just saying “it’ll be fine, we can just go melee kill.” But it’s still enough hit points (and enough hull sections) that they don’t just get blasted to flinders in a round. (Unless they go bother a ship of the line.) I also have fewer cannon per ship because they are newer, rarer, and more expensive in Golarion – FasB lets you pack like 4 9-pounders into a single hull section so “28-gun” and “49-gun” ships exist – in my game it’s more like 4 cannon a side is a well armed craft. (And also not hours of dice rolling for a single round of combat).

Anyway, once you have your ship and cannon, you gain the weather gage, maneuver trying to get closer or farther away; conduct maneuvers while trying to line up cannon shot, and so on. These are similar to these other naval rulesets.

Part of the real magic, however, is the range bands and speed checks. This is what makes the battles feel naval and not like sitting slugfests. The Skull and Shackles rules just make this “2 out of 3 sailing checks and you catch ’em”. But I bring in some ideas from my chase rules that make the positioning important, and not just a preface to a static combat. Your ship’s speed turns into a bonus to a Profession: Sailor check and if you can beat the other ship by 5, you can close (or increase) the range by a band.

We’ve been using these rules a lot over years and it’s very dynamic. You pull a little closer – now you’re in Medium range and can bring those 12-pounders (and fireballs) to bear! Oh no, they pulled away to Long range, try to hit their sails with the long nine chase gun! It hits the magic ratio of 2/3 of the combat is naval before finally 1/3 devolves into normal Pathfinder combat, and a full on naval battle beween fully armed ships with similarly-leveled crew is a showcase event that can take most of a game session. And it’s not a completely abstract minigame; you’re throwing your usual spells and shooting your usual bow or musket at the other ships.

Enjoy, and let me know how you find them!